April 6, 1935 - LIFE ON A FREIGHTER

The story of three weeks aboard a cargo ship, where people did exactly what they pleased, which was usually nothing.

The Washington Daily News—Saturday—April 6—1935 Page 13

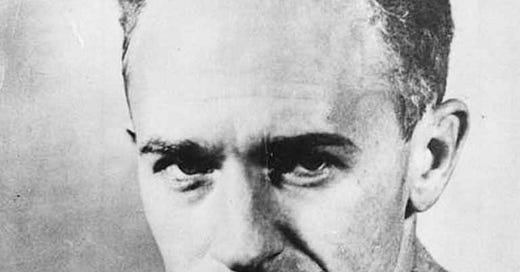

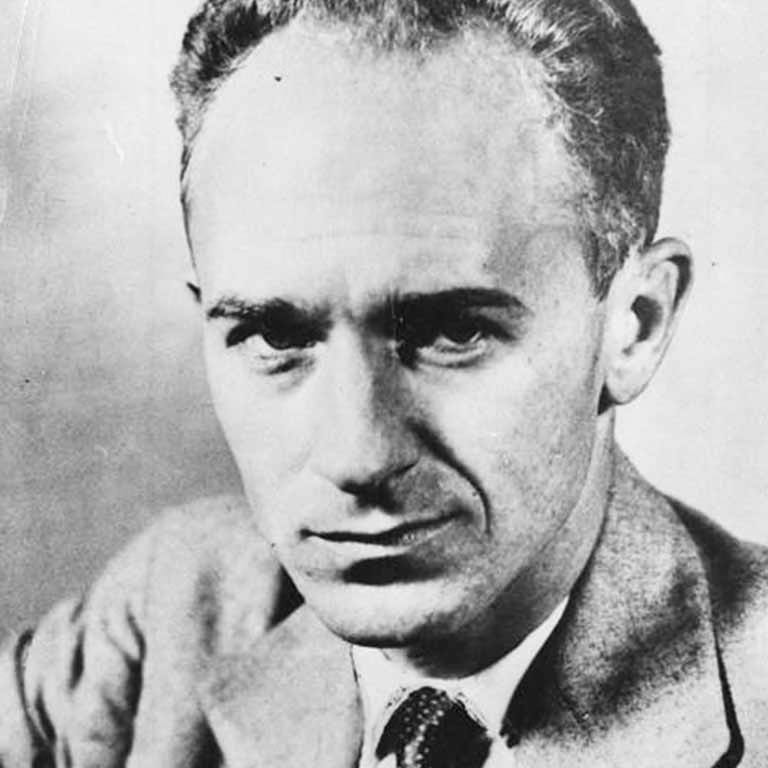

LIFE ON A FREIGHTER By ERNIE PYLE

WE WENT aboard her exactly at noon. It was pouring down rain, and she looked sort of funny as we came around the end of the pier at San Pedro and saw her lying there, her decks piled high with lumber.

She was a freighter all right. That’s what we wanted, and that’s what we got. Traveling as passengers on a cargo ship. There’s nothing like it in the world.

It took us three weeks to come from San Pedro (Los Angeles) to Philadelphia. I wish it had taken three years. Getting off that ship, when the time came, seemed to me almost the saddest thing that had ever happened in the lives of the seven passengers aboard.

The name of our ship was the Harpoon. Her captain was John McKown, a fine man if there ever was one—20 years in sail, 17 years in steam, his father and three brothers all sailing captains.

The Harpoon was not such a small boat. Of course she looked tiny alongside the floating hotels, but she was 9000 tons and rode the seas like a cowboy. She wasn’t the “dirty old freighter” of tradition, but clean and well-kept.

She was loaded to the water line; we even had to leave considerable cotton on the dock. Her fore and after decks were piled 10 feet deep with lumber, held on with huge chains. In the hold was more lumber, thousands of bales of cotton, more thousands of bales of old inner tubes, old auto radiators in bulk, drums of oil, sacks of some new kind of feed called wood meal. And last, but I assure you not least, 50,000 gallons of sardine oil, which smells not like a sardine, but much worse.

Of passengers there were seven, three women and four men. They were seven people made for just such a voyage. They were people of “freighter temperaments.” The officers liked us, and we liked them. There were four deck officers, four engineers, two cadets and the radio operator. All the rest of the crew were Filipinos. Any one of the ship’s four lifeboats, built for 40 people apiece, could have held everybody on board, including the three pet dogs.

WE WERE told to board her at noon, for we were sailing at 2. But in the manner of freighters, the winches were still grinding away at 2, and the sailing was postponed till 4, then 9, then 11, and finally at 2 o’clock the next morning we slipped lonesomely away from the dark pier.

Our cabin, which happened to be the best of the seven aboard, was a corner one, with porthole in two sides. It was large, freshly painted white, with a rug in the center of the floor, double-decked bunks with reading lights, a lounge against the opposite wall, a chiffonier, a washbowl, a closet in the corner for clothes, and an electric fan.

I wish I could put into words the informality of life on a freighter, the timelessness it seems to generate, the beauty of a relaxed purposelessness. There was no routine whatever, except eating. The days went by without pattern. You did what you pleased, which was usually nothing.

An example of what I mean was shuffleboard. On the boat deck was painted the shuffleboard court, or whatever you call it. Nobody paid any attention to it for about ten days. Then one day the British girl on board got out the disks and cue, and played for about five minutes. Then she put them away. “It’s too much trouble,” she said. The shuffleboard was never used again.

● ● ●

BREAKFAST was at 8, served by Tommy, the smiling Filipino mess boy (who was also our cabin boy) in the little dining room with its one long table. Officers and passengers ate together. Every morning I ate breakfast in pajamas and bathrobe.

After breakfast you might go back to bed, or go up and sit on deck (with or without dressing), or walk around, or sit and read, or just stare at the water, or talk to somebody, or go up on the bridge or down in the engine room. It didn’t make any difference. Nobody cared.

I have stood on the focsle head for three hours straight just watching the sharp boy slice the blue water, watching for a flying fish or a dolphin, full of feeling that it didn’t matter whether I saw one or not. Some days I saw some, some days I didn’t.

Lunch was served at 12. In the afternoon, again there wasn’t any program. Usually you fell asleep for an hour or so somewhere. You sat in the sun and baked, or in the shaded deck house and read. At 3 p.m. Tommy served tea. It seemed very funny to be drinking tea at 3 on a freighter. And always one or two sweaty engineers, up from the hot depths in their greasy overalls, sat with us, chatting and gabbing and drinking their coffee.

Sometimes we went out on the piled lumber and walked up and down for half a mile or so before dinner. Dinner was at 5. After dinner we saw the sunset. By 6 the captain was always back at the head of the table, ready to play poker. Also the first engineer, the second mate, the radio operator and a few passengers. The game usually lasted till about 11.

Those of us who didn’t play poker sat on deck at night, silent under the rich tropic skies...figuring out the Southern Cross, and the False Cross, and Orion’s Belt, really aware for the first time in years that we’ve got a sky that’s got stars in it.

● ● ●

NOT A single stateroom door was locked or even closed, during the entire voyage. You just pulled a curtain over it, and that was all. At night, down around the Canal, we slept on deck.

It was a complete life of freedom. One morning I was up and on deck at 3:30, for no other reason than that I just felt like doing it, and wanted to see the hot sun come up. Again I helped the sailors with their painting, and it was fun. One Sunday morning one of the Filipino deck hands cut my hair. One day I wandered down in the engine room, and the temperature was 156. One morning I jumped out of bed and landed smack on Calico, the captain’s pet police dog who had simply walked into the stateroom during the night and gone to sleep. We sailed all one day thru schools of dolphins, thousands of them. The big ones swim three abreast, about three feet apart, and come marching thru the crest of a wave like three soldiers. The mates never wore shirts, except at meal times, and sometimes the captain didn’t. We knew every Filipino in the crew, not by name but by face, and we spoke and smiled at each other always as they went about their work.

● ● ●

AS FOR the more material facts of life on a freighter: the food was good; not elaborate, but wholesome and of good variety; the fare was $95 per person; we brought the car along, and it rose right out on top of the lumber, tied down of course and with a tarpaulin over it, and we could walk out and look at it whenever we wanted to.

It was rather chilly the first three days out of Los Angeles. From there to the Canal the sea was like glass, and it was hot. From the Canal till we got close along shore in the lee of Haiti (two days) a 40-mile wind made it cold and rough. But past Cuba it warmed up and smoothed down, and stayed that way till within one day of Philadelphia.

I wouldn’t advise anybody to travel on a freighter. First, if too many people take it up, it will spoil everything. And second, unless you happen to have that “freighter temperament” you might go crazy, and that would be awful.

---

💛 **Enjoyed this post?** Your support helps The Ernie Pyle Legacy Foundation continue to transcribe and promote Ernie’s work. Please click the link below to donate.