AUGUST 29-1935-Fundy’s Giant Tides Cause Falls to Reverse Themselves

The Washington Daily News—Thursday—August 29,—1935

Fundy’s Giant Tides Cause Falls to Reverse Themselves

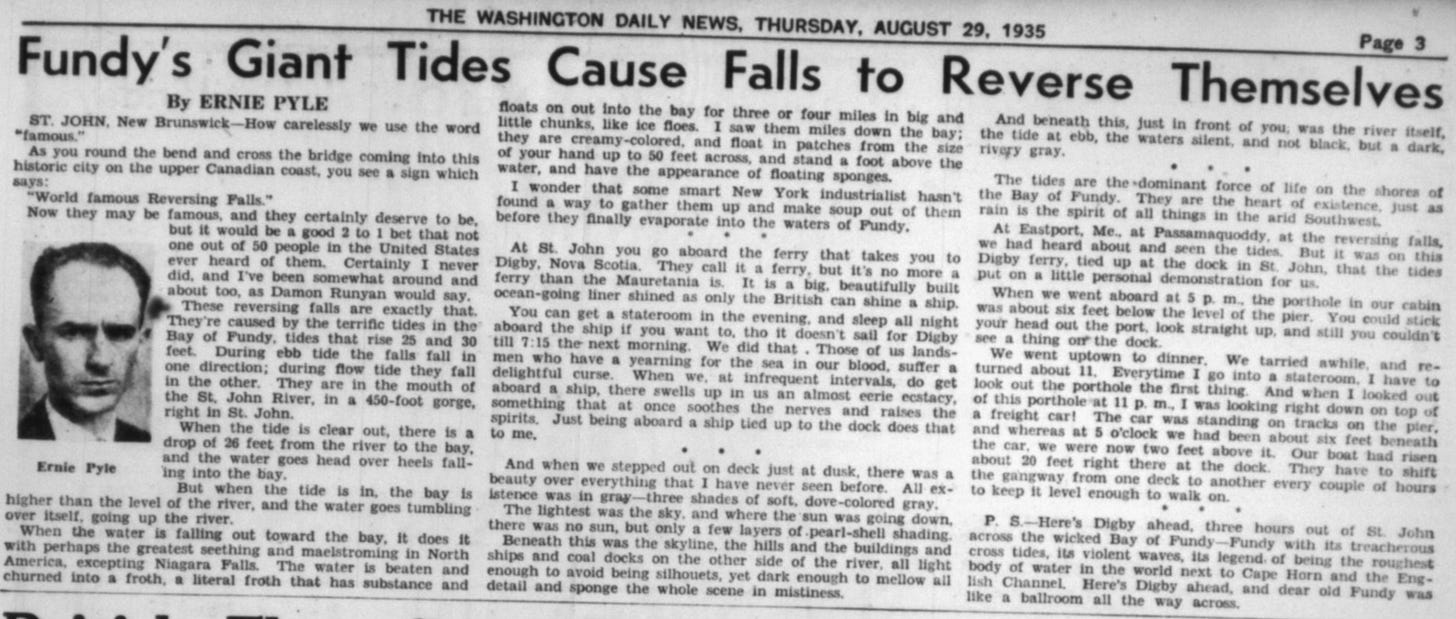

Ernie Pyle

ST. JOHN, New Brunswick—How carelessly we use the word “famous.”

As you round the bend and cross the bridge coming into this historic city on the upper Canadian coast, you see a sign which says: “World famous Reversing Falls.”

Now they may be famous, and they certainly deserve to be, but it would be a good 2 to 1 bet that not one out of 50 people in the United States ever heard of them. Certainly I never did, and I’ve been somewhat around and about too, as Damon Runyon would say.

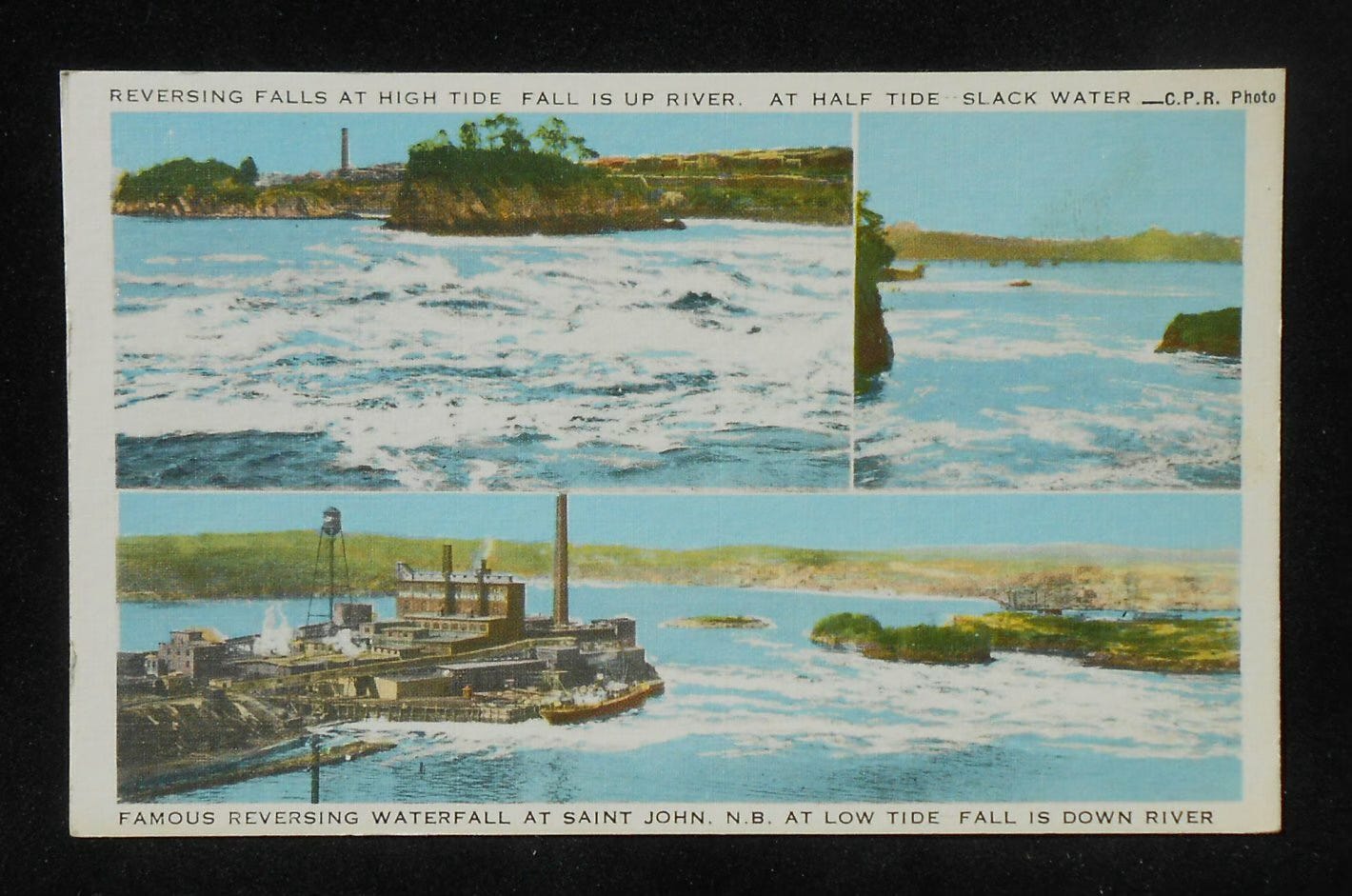

These reversing falls are exactly that. They’re caused by the terrific tides in the Bay of Fundy, tides that rise 25 and 30 feet. During ebb tide the falls fall in one direction; during flow tide they fall in the other. They are in the mouth of the St. John River, in a 450-foot gorge, right in St. John.

When the tide is clear out, there is a drop of 26 feet from the river to the bay, and the water goes head over heels falling into the bay.

But when the tide is in, the bay is higher than the level of the river, and the water goes tumbling over itself, going up the river.

When the water is falling out toward the bay, it does it with perhaps the greatest seething and maelstroming in North America, excepting Niagara Falls. The water is beaten and churned into a froth, a literal froth that has substance and floats on out into the bay for three or four miles in big and little chunks, like ice floes. I saw them miles down the bay; they are creamy-colored, and float in patches from the size of your hand up to 50 feet across, and stand a foot above the water, and have the appearance of floating sponges.

I wonder that some smart New York industrialist hasn’t found a way to gather them up and make soup out of them before they finally evaporate into the waters of Fundy.

● ● ●

At St. John you go aboard the ferry that takes you to Digby, Nova Scotia. They call it a ferry, but it’s no more a ferry than the Mauretania is. It is a big, beautifully built ocean-going liner shined as only the British can shine a ship.

You can get a stateroom in the evening, and sleep all night aboard the ship if you want to, tho it doesn’t sail for Digby till 7:15 the next morning. We did that. Those of us landsmen who have a yearning for the sea in our blood, suffer a delightful curse. When we, at infrequent intervals, do get aboard a ship, there swells up in us an almost eerie ecstasy, something that at once soothes the nerves and raises the spirits. Just being aboard a ship tied up to the dock does that to me.

● ● ●

And when we stepped out on deck just at dusk, there was a beauty over everything that I have never seen before. All existence was in gray—three shades of soft, dove-colored gray.

The lightest was the sky, and yet the sun was going down, there was no sun, but only a few layers of pearl-shell shading.

Beneath this was the skyline, the hills and the buildings and ships and coal docks on the other side of the river, all light enough to avoid being silhouettes, yet dark enough to mellow all detail and sponge the whole scene in mistiness.

And beneath this, just in front of you, was the river itself, the tide at ebb, the waters silent, and not black, but a dark, wavy gray.

The tides are the dominant force of life on the shores of the Bay of Fundy. They are the heart of existence, just as rain is the spirit of all things in the arid Southwest.

At Eastport, Me., at Passamaquoddy, at the reversing falls, we had heard about and seen the tides. But it was on this Digby ferry, tied up at the dock in St. John, that the tides put on a little personal demonstration for us.

When we went aboard at 5 p.m., the porthole in our cabin was about six feet below the level of the pier. You could stick your head out the port, look straight up, and still you couldn’t see the top of the dock.

We went uptown to dinner. We tarried awhile, and returned about 11. Every time I go into a stateroom, I have to look out the porthole the first thing. And when I looked out of this porthole at 11 p.m., I was looking right down on the top of a freight car! The car was standing on tracks on the pier, and whereas at 5 o’clock we had been about six feet beneath the car, we were now two feet above it. Our boat had risen about 20 feet in the six hours we were away. They have to shift the gangway from one deck to another every couple of hours to keep it level enough to walk on.

● ● ●

P. S.—Here’s Digby ahead, three hours out of St. John across the wicked Bay of Fundy—Fundy with its treacherous cross tides, its violent waves, its legend of being the toughest body of water in the world next to Cape Horn and the English Channel. Here’s Digby ahead, and dear old Fundy is like a ballroom all the way across.

💛 **Enjoyed this post?** Your support helps us continue to transcribe and promote Ernie’s work. Please click the link below to donate.